Vukovar

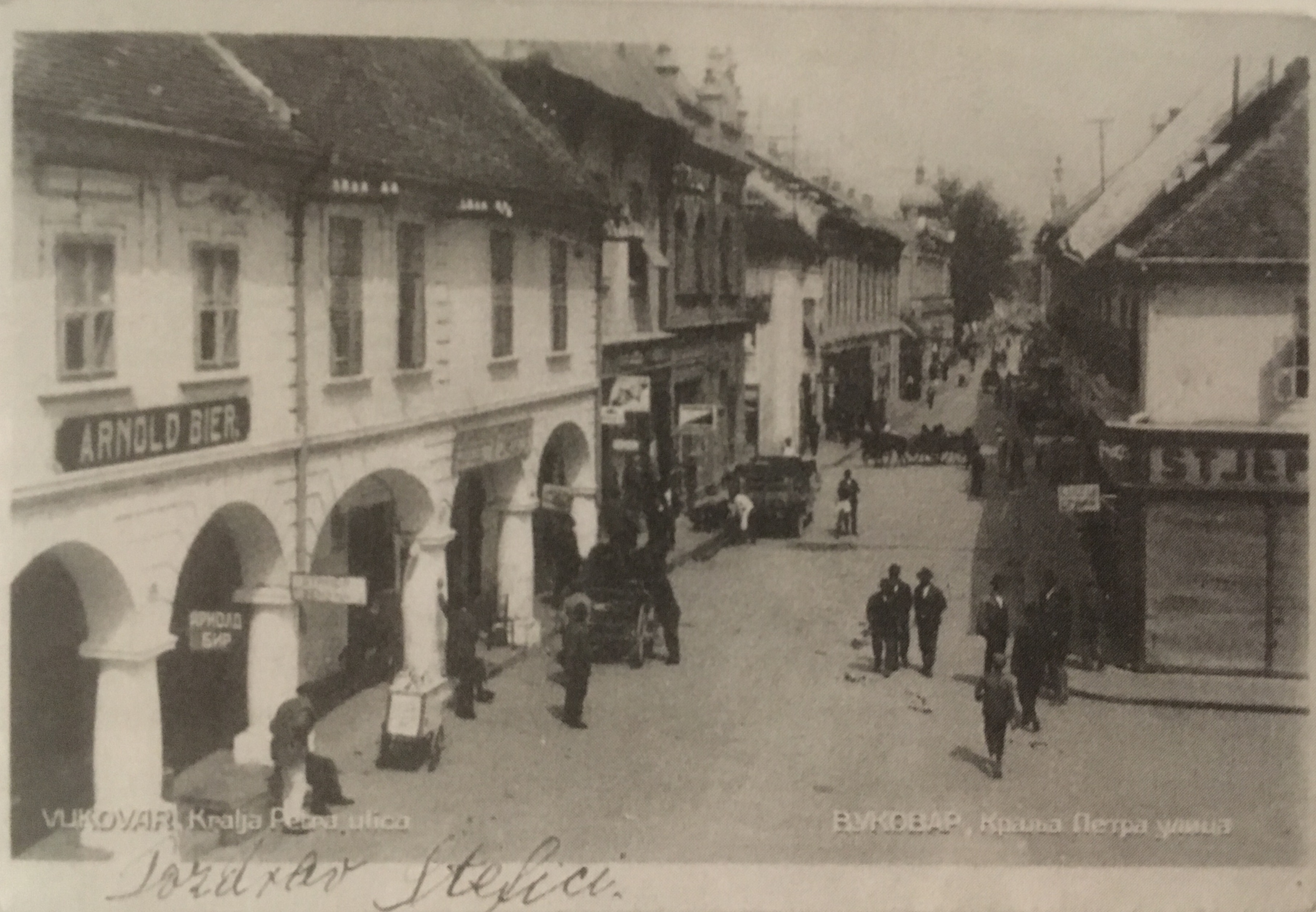

The city of Vukovar lay in the northeastern reaches of the Independent State of Croatia, on the border with Hungarian-occupied Bačka, today part of Serbia. Exceptionally diverse, Vukovar was home to fourteen ethno-confessional groups on the eve of the Second World War—Croats, Serbs, Jews, Germans, Roma, Hungarians, Slovaks, Czechs, Ruthenians, and others. The 1931 census listed 10,862 inhabitants in Vukovar, among them 48% Croats, 21% ethnic Germans, 20% Serbs, and 3% Jews. Vukovar’s Jewish community was an integral part of the city’s everyday life before the Holocaust. Housing the seat of the Upper Rabbinate of Syrmia, the community administered two synagogues for a time, until the older one was sold to the Calvinist congregation in 1894. The new synagogue, a beautiful edifice completed in 1888, was the pearl of the city’s skyline.

Located in the middle of the fertile flatlands of the Pannonian basin, the Vukovar area was well-developed agriculturally. The city’s economic significance was further reinforced by its place among the most industrialized localities in the interwar Kingdom of Yugoslavia. In 1941, after Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy established the Independent State of Croatia under the rule of the radical right-wing Ustaša movement, Vukovar became the administrative center of the Grand Parish of Vuka (“Velika župa Vuka”), one of the new state’s twenty-two administrative regions. The Grand Parish of Vuka corresponded to the borders of the historical region of Syrmia, a vast area of some 6,800 square kilometers reaching all the way to Zemun, today part of the metropolitan area of Belgrade, capital of Serbia.

With the creation of the Independent State of Croatia, the Jewish community of Vukovar—by 1941 numbering around 600 people—came under an attack from which it would never recover. The last rabbi to serve the community before its destruction was Dr. Israel Scheer (1898-1941), arrested shortly after the establishment of the Ustaša state and killed in Jasenovac death camp.

Vukovar’s Ustaša authorities forced notable Jewish and Serb men to report to the police on a daily basis; most of these men were organized into forced labor squads. Jewish survivor Jelena Malević (b. Fuchs) remembers that Jewish women were organized in forced labor units already in April and tasked with scrubbing the streets and public toilets. The movement of the “undesirables” was severely limited. Jews, Serbs, and Roma had to obtain police permits for any kind of travel.

In April-May 1941, Vukovar’s Ustaša authorities expropriated Serb and Jewish property in a single action, merging the campaigns of extortion against the two groups. Vukovar’s Ustaša and ethnic German authorities also used the “contribution” or “tribute” payment—both euphemisms for extortion—to get their hands on the property of the “undesirables.” Starting on April 25 and over the next few days, they arrested forty Jewish notables from Vukovar. The men were stripped of all valuables and, on May 3, 1941, four of them were brought to the town’s Ustaša headquarters and ordered to collect a “tribute” of three million Yugoslav dinars (the new currency, “kuna,” had not yet been established), with promises to protect the Jewish community upon payment. Half the “tribute” was to be collected by 7 PM on May 5, and the other half by 7 PM on May 7. After signing the document, the Jewish men were released. Local Ustaša commander Luka Puljiz threatened the Jews with harsh measures should they fail to collect the tribute. The community flurried to Jewish homes across the town but was 15,600 dinars short for the first installment. The “tribute” was finally paid in full on May 12, but arrests and persecution resumed despite the authorities’ promises.

Killings began immediately after the establishment of the Independent State of Croatia on April 10, 1941. On April 11, the day Vukovar Ustašas took control of the city, the very first person whom Ustaša militias arrested was Josip Herzl, a prominent Jewish physician who was never seen again. On April 12-13, Ustašas arrested the members of the Jewish Community council, releasing them a few days later; like most of the community, these men were eventually arrested again, deported, and killed in Jadovno and Jasenovac death camps. Ustaša authorities arrested a second, larger group on April 26, releasing them after the “contribution” payment. The third mass arrest action occurred sometime in mid-summer 1941, when several dozen Jewish young men were taken to Jasenovac death camp. The fourth mass arrest took place the night between August 15 and 16, 1941, when Ustašas interned a group of “wealthier Jews” in the Vukovar synagogue, which served as a temporary concentration camp until the men were transferred to Jasenovac death camp on November 8. Another telling anti-Jewish incident in Vukovar occurred around Christmas 1941, when, after a screening of the Nazi anti-Jewish propaganda film Jud Süss at the local cinema, a mob smashed the windows on the house of Aleksandar Steiner.

As the measures against them gained momentum, Jews reached for religious conversion in hope of escaping their “racial” Jewishness.

The regime, however, continued its policy of destruction without regard for individual Jews’ religious status.

As the regime instructions specified, a Jew’s conversion meant nothing because the racial laws took precedence.

In Vukovar, the number of Jewish conversions spiked in December 1941 and January 1942, around the same time as the

regime invested the most sustained effort to forcibly convert local Eastern Orthodox Serbs into Roman Catholic Croats.

The next deportation action in Vukovar occurred in June 1942, when a large number of Jews were taken to

the nearby Tenja concentration camp. The bulk of Vukovarian Jews were deported to death camps on

July 27, 1942. A small number of Jewish women, who received a stay of deportation, were deported to death

camps in spring of 1943.

The main mass killing site in the Vukovar area was a wooded place on the outskirts of the city

called “Dudik.” A group of Vukovarian Jews were brought to dig long ditches and handle the corpses

after mass shootings. The victims of these killings were mostly Serbs, but also some Jews, “renegade”

Croats, and others.

Like many Serbs, many Jews joined armed resistance in response to Ustaša persecution,

as well as a growing number of Croats and other groups as the Ustaša tenure in power continued.

Jewish survivor Alfred Pal survived as part of the communist Partisan resistance in Yugoslavia.

His brother, Aleksandar Pal, linked himself to the communist Partisan rebels in one of the

villages near Vukovar, but did not survive the war. Physicians Đuro Oberson and Rudolf Bienenfeld with

several of their family members also survived by joining the Partisans, as well as Jelena Malević with

her mother Katica Fuchs (b. Holzer) and her niece Mirjam Delić (b. Stern).

Sixty-three Vukovarian Jews survived the Holocaust. The great majority never made Vukovar their home again.

The Jewish community of Vukovar was never rebuilt.dar Steiner.

Source Documents

Testimony of Ivan Kostenac

Memo on the deportation of Serbs and Jews suspected of communism

Ljudevit Pollak, rectitude confirmation request

Elsa Klein’s request for permission to convert to Catholicism

Rejection of Elsa Klein’s request to convert to Catholicism

Herzog Vjera, permission form for conversion to Catholicism

Vukovar police delivers profits from the sale of Jewish signs to city council

Ustaša request for a report on the number of Jews left in Vukovar

Ustaša manual headcount of Jews left in Vukovar

Ustaša report on the number of Jews left in Vukovar

Testimony of Đuro Oberson

Testimony of Rosa Oberson