Jasenovac

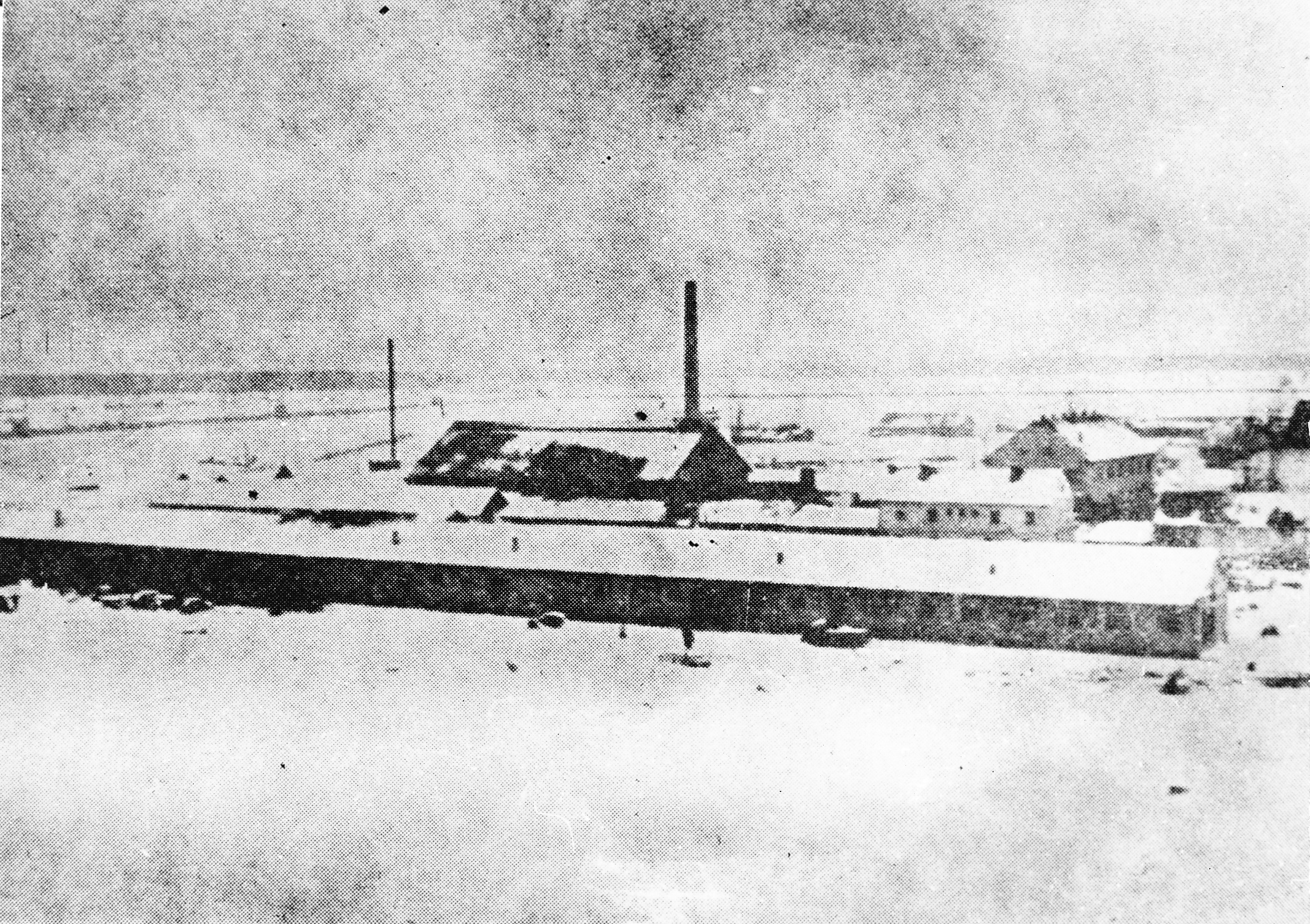

The Jasenovac camp complex can be called a hybrid camp facility in the sense that it functioned both as a site of forced labor, as a transit camp, and as a mass-killing center. It included multiple camps, external labor facilities and killing sites. The main camp, Jasenovac, III was located just west of the town of Jasenovac.

The first planning for the camp complex began in late July 1941. The Ustaša regime chose the area around the town of Jasenovac in Western Slavonia for several reasons. For one, an existing network of warehouses and workshops confiscated from a local Serb resident named Jovan Bačić offered a foundation for production. The regime also planned to utilize forced labor to drain the surrounding wetland by building embankments along the Sava River and its tributary Veliki Strug. Finally, the flat and marshy landscape of the area made it easy to defend against attacks and made it difficult for prisoners to escape.

The first two camps, Jasenovac I and II, were created in late August 1941 near the villages of Krapje and Bročice respectively. Most of the prisoners in the two camps were Serbs and Jews. In harsh conditions, they carried out forced labor on an embankment along the river Veliki Strug. Because of flooding the two camps were abandoned in mid-November 1941.

The main camp complex, Jasenovac III, was located a few kilometers east of the town of Jasenovac.

It is commonly referred to as the “brickyard” (Ciglana) because of a large brickyard within

its premises. Other productive facilities included a chain factory and a sawmill.

Though preparations for its construction began earlier, it was first after the closure of

Jasenovac I and II that a substantial number of prisoners started to arrive at Jasenovac III.

Some prisoners carried out forced labor in different workshops while others worked at external

labor sites. In 1942, many of the prisoners worked on an embankment just east of the camp premises.

Others cut wood or worked at farms that supplied food to the guard force and, to a much lesser extent,

the prisoners. Similarly to the Kapo system in SS concentration camps, there was an internal

administration of prisoner functionaries.

In early 1942, two other camps were included in the camp complex. The first, Jasenovac IV,

comprised a tannery located within Jasenovac town, surrounded by barbed wire. The second,

Jasenovac V, was an an old penitentiary in the small town of Stara Gradiška, which was converted into

a concentration camp. This camp was located around thirty kilometres east of Jasenovac III.

The Jasenovac camp complex was administrated by the Ustaša Defense (Ustaška obrana), a paramilitary

organization which throughout most of its existence was headed by Vjekoslav Luburić. The executive

force of the Ustaša Defense was the 1st Ustaša Defense Unit (Ustaški obrambeni zdrug), which guarded

the camp complex. The unit was also responsible for the security for the wider surrounding area and

committed numerous atrocities against the local Serb population.

Most of the people deported to the Jasenovac Camp Complex were Jews, Roma, and Serbs. However, there were also many Croat and Bosniak political prisoners who for the most part were incarcerated in Jasenovac V, the Stara Gradiška Camp. This camp also served as a transit site for thousands of primarily Serb prisoners who were deported to Nazi Germany as forced laborers.

The size of the prisoner population in the main camp, Jasenovac III, fluctuated, but the Ustaša camp personnel usually capped the number at 3000, corresponding to the requirements of the labor force. As in SS camps that combined forced labor and extermination, such as Auschwitz-Birkenau, the guard force siphoned arriving prisoners deemed capable of labor into the workforce. The rest were murdered.

The main killing area was the area of Gradina located on the opposite of the

Sava River in what is today Bosnia and Herzegovina. The camp guard force murdered

most of the victims with weapons such as knives, mallets, and hammers.

The main camp, Jasenovac III, operated until the end of April 1945. During

this month, the guard force systematically excavated the mass graves and destroyed

the remains in open pits in order to conceal the crimes. Before the last camp guard

personnel withdrew on May 1, 1945, they demolished the camp and destroyed several

buildings in the town of Jasenovac.

The question of the number of victims of the Jasenovac camp complex has been

a sensitive topic, especially in the Republic of Croatia and in the Republic of

Serbia. In the years following the end of the Second World War, the authorities

in the Federal Republic Yugoslavia inflated the victim figure of the camp complex.

Research suggests this was done deliberately in a bid to ensure more reparations.

The commission tasked with assessing wartime losses in postwar Yugoslavia, the

Commission for Investigating the Crimes of the Occupiers and their Collaborators,

asserted that between 500,000 and 600,00 people perished in the camp complex; a

claim that most experts on the topic now see as improbable.

So far, the Jasenovac Memorial Museum in Croatia has identified the names of

83,145 people who perished in the camp complex. These include 47,627 Serb victims,

16,173 Roma victims, 13,116 Jewish victims as well as 5383 Croat and Bosniak

Victims. However, it is important to keep in mind that this figure does not

encompass all victims, and efforts to compile victim information are ongoing.

While methodological challenges make establishing the exact figure difficult,

there is a growing consensus in the academic communities in the Republic of

Croatia and the Republic of Serbia concerning the number of victims. Current

objective estimates tend to range from 90,000 to 130,000 victims.

Despite a prolific commemorative culture in the late 1940s and 1950s in the

Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, it was not until 1966 that a monument

was erected at the former camp site. Various reasons have been cited in scholarly

literature to explain this delay. Firstly, the prevailing memorial culture at the

time often emphasized armed resistance and partisan heroism rather than civilian

suffering. Additionally, as the atrocities at Jasenovac were perpetrated not by

external occupying forces but by the domestic Ustaša regime, commemorating the

site was deemed a sensitive matter that could hinder inter-ethnic reconciliation

and challenge the narrative of "brotherhood and unity." Furthermore, historian

Dr. Heike Karge argues that the manipulation of victim figures by the political

elite in Belgrade heightened sensitivities and paralyzed decision-making regarding

how to appropriately commemorate the site.

The impetus to create a monument largely stemmed from grassroots efforts, particularly survivor

organizations, placing pressure on the Association of Veterans of the People’s Liberation War,

the primary political actor in the sphere of memory politics in socialist Yugoslavia. With funding

from the federal government and private donations, renowned architect Bogdan Bogdanović designed a

24-meter-tall monument resembling a flower in blossom. Bogdanović opted for a representation that

evoked contemplation rather than stark depictions of horror and destruction, with the flower symbolizing

hope for renewal and reconciliation. The monument was unveiled to the public in July 1966.

Since the secession wars in the 1990s, questions of how to commemorate the Jasenovac camp complex have

frequently animated and accompanied political tensions in the region. As a consequence of the

breakup of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, there is now a memorial site at the

site of Jasenovac III in the Republic of Croatia and a memorial at the site of Gradina in the

political entity of Republika Srpska in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The two memorials sites are not

officially connected.

Source Documents

Missive Stating that the Jasenovac Camp Complex Can Receive an Unlimited Number of Prisoners

Excerpt about Nutrition in Jasenovac III from a Report by Survivor Vojislav Prnjatović

Letter card by Jasenovac-prisoner Ilija Ivanović to his mother Jovanka Ivanović

Letter Containing a Plea for the Release of Hugo Štern from the Jasenovac Camp Complex

Testimony by Sofija Spoljarić about her Imprisonment in the Women’s Section of Jasenovac III

Excerpt from the Postwar Testimony of Maja Buždon, Commander of the Women’s Section of the Stara Gradiška Camp

Extract from Report About Intimate Relations Among Female Inmates in the Stara Gradiška Camp

Excerpt from Cadik Braco Danon’s Memoirs about his Encounter and Conversation with a Guard at Jasenovac III

Excerpts from the Memoirs of Ilija Jakovljević about his Conversations with Ustaša Nikola Gagro

Excerpt from the Memoirs of Survivor Đorđe Miliša about Selections during Roll Calls

Excerpt from the Testimony of Egon Berger about the Crematorium

Excerpt from the Postwar Testimony of Ljubomir Miloš about Killings at the Jasenovac Camp Complex

Missive Notifying of the Shooting of Sixteen Prisoners in Jasenovac II

Excerpt From the Testimony of Jakov Finci About the Prisoner Outbreak from Jasenovac III on April 22, 1945

Missive issued by the Police Authorities in Varaždin about Escaped Prisoners from the Jasenovac Camp Complex

Excerpt from the Testimony of Survivor Albert Maestro about Forced Singing at the Jasenovac Camp Complex

Excerpt from Article in the Ustaša Press about a Reporter’s Visit to the Jasenovac Camp Complex